Sculptor, Installation Artist, and Author

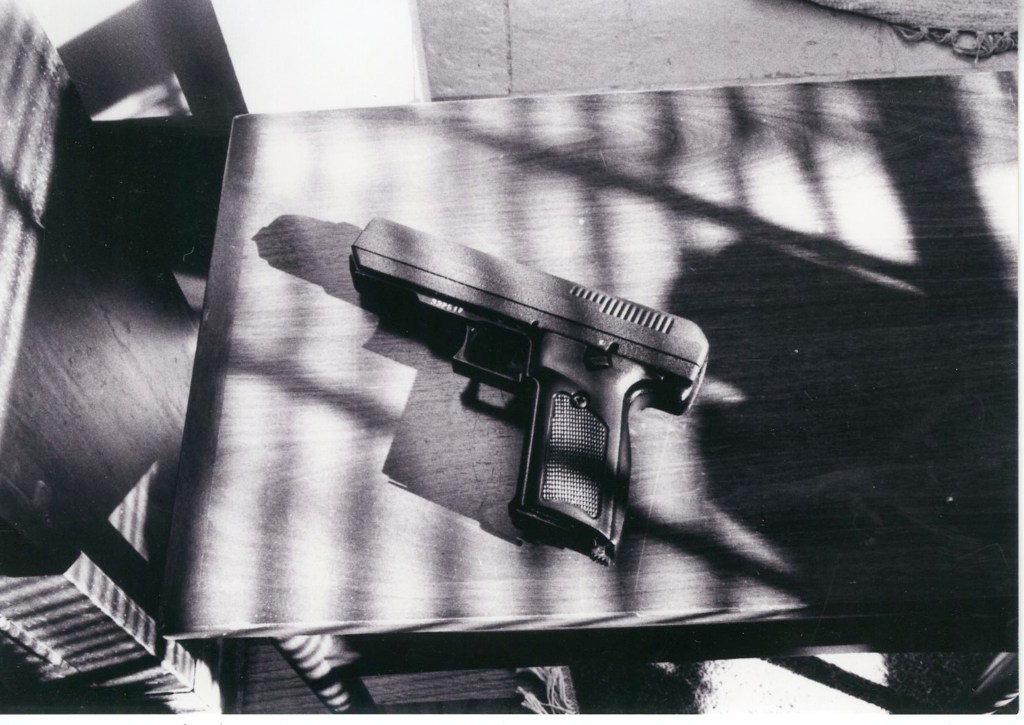

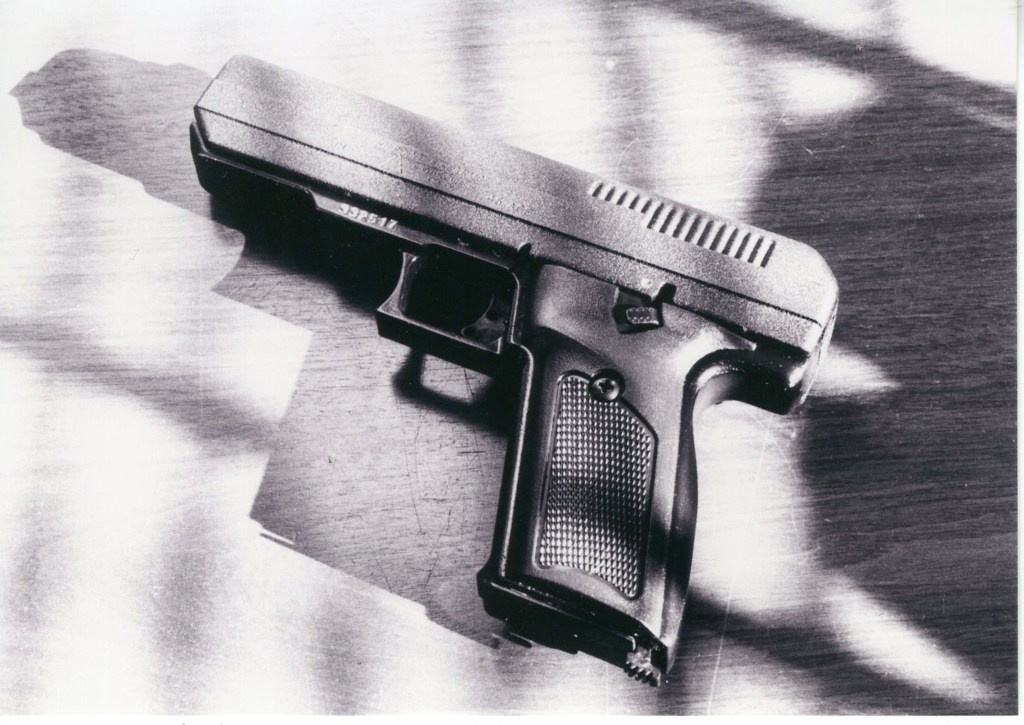

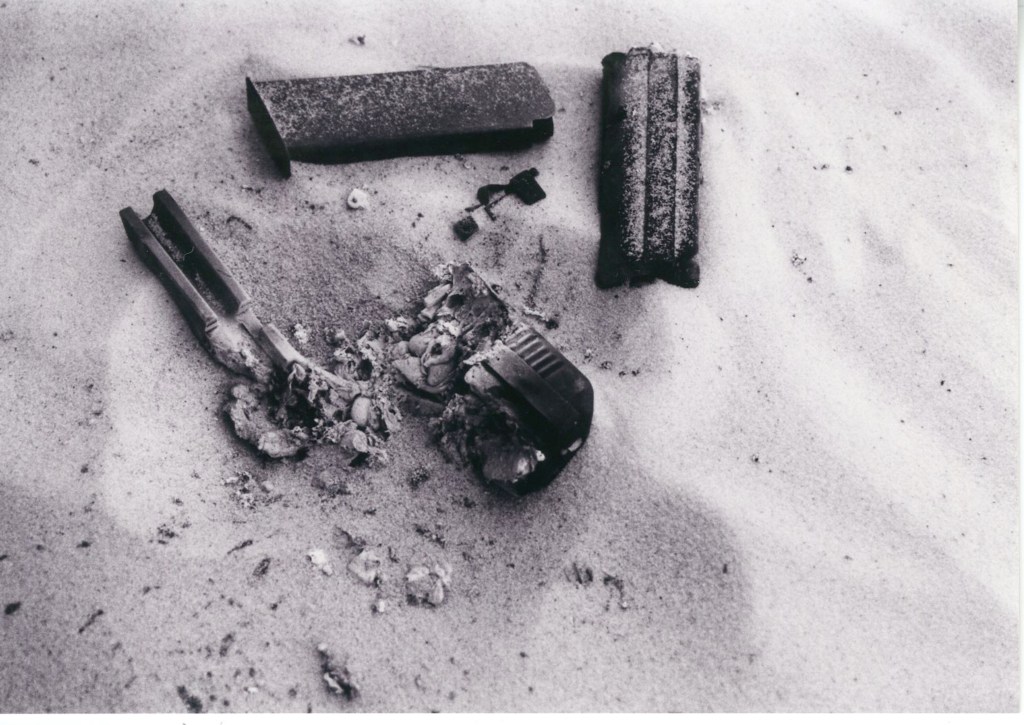

I decided to melt a gun. This was quite an interesting adventure as I had never held a gun before. I purchased a brand new handgun from a dealer who kept questioning me about what I was going to do with it. I thought if I told him, he might not sell it to me, so I kept saying that I wasn’t sure, but that I planned to make art out of it. I had to take a test and get a license before I could buy the gun. During the melting process, it gave off terrible black smoke, sparks flew everywhere and it refused to melt into one neat piece. It remains a pile of crumbling metal. I have mounted it three different ways, not being satisfied with my first attempts. The images here are from the latest framing.

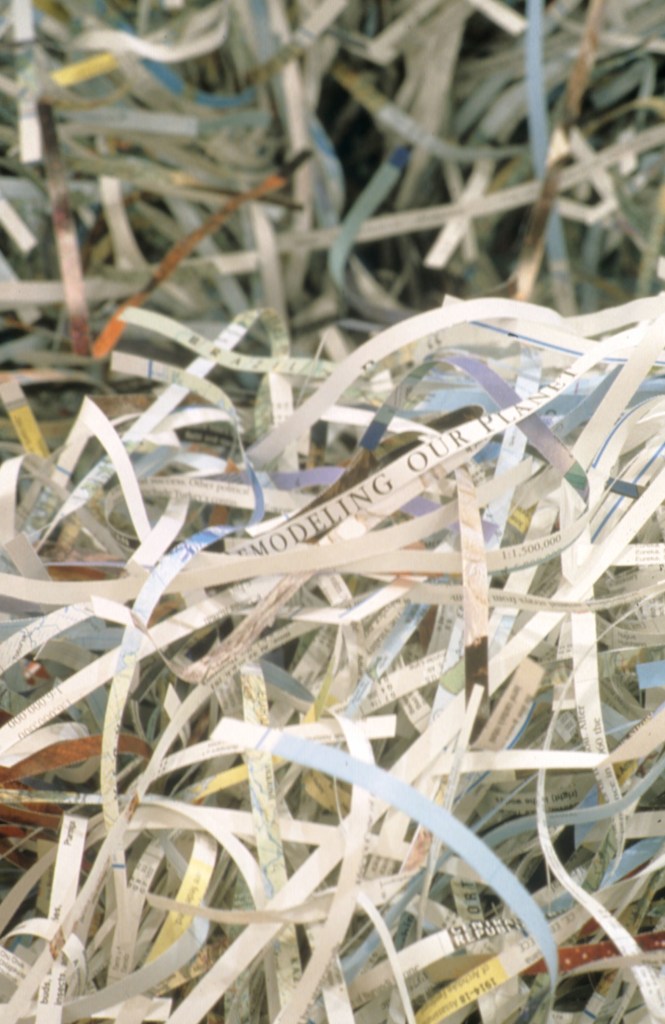

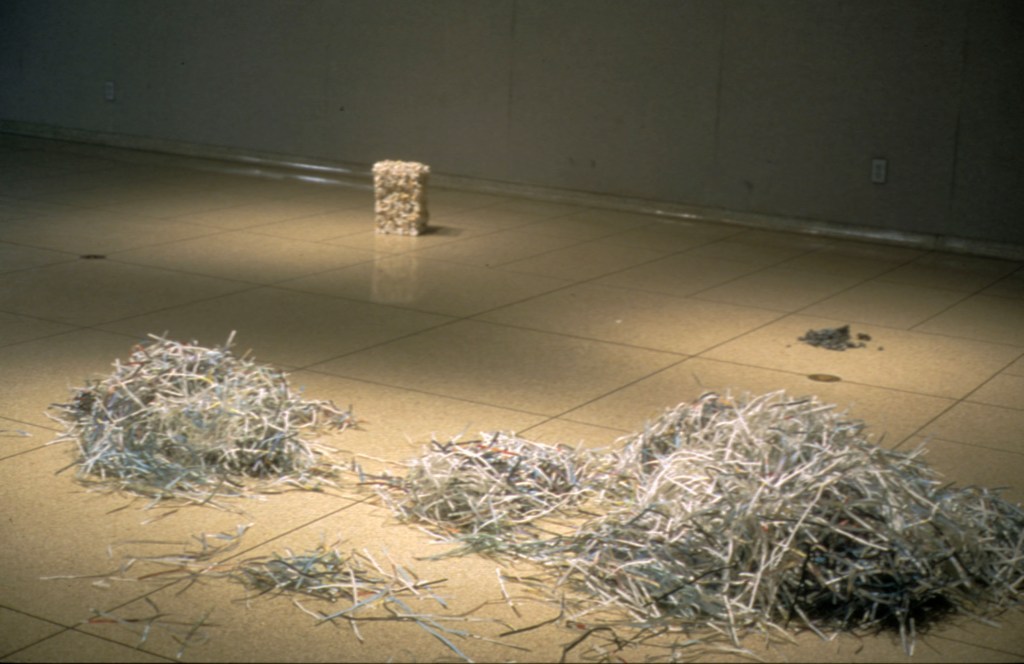

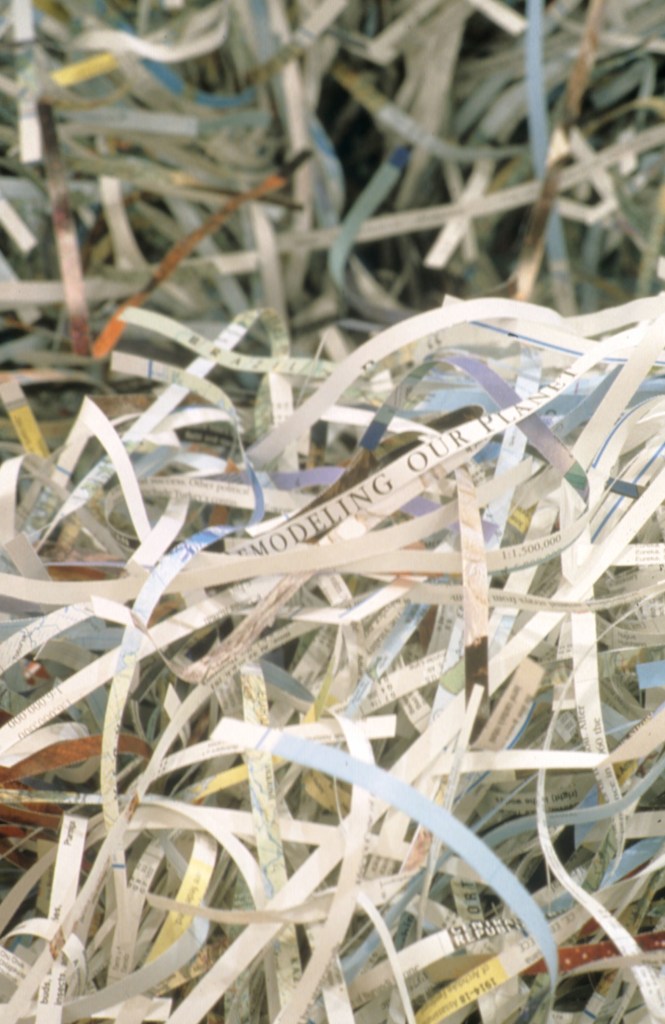

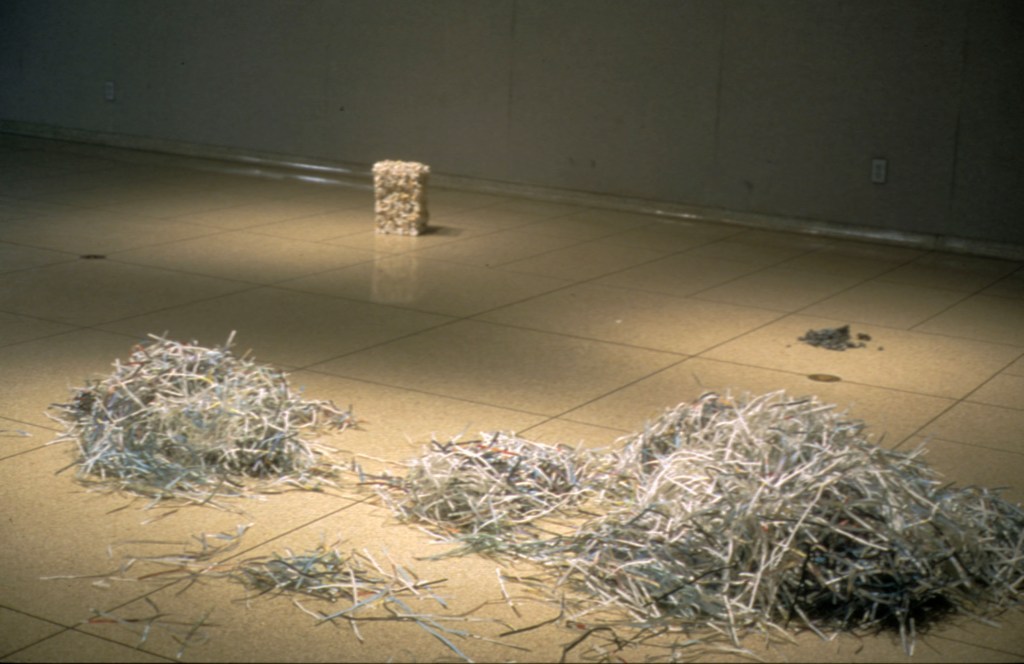

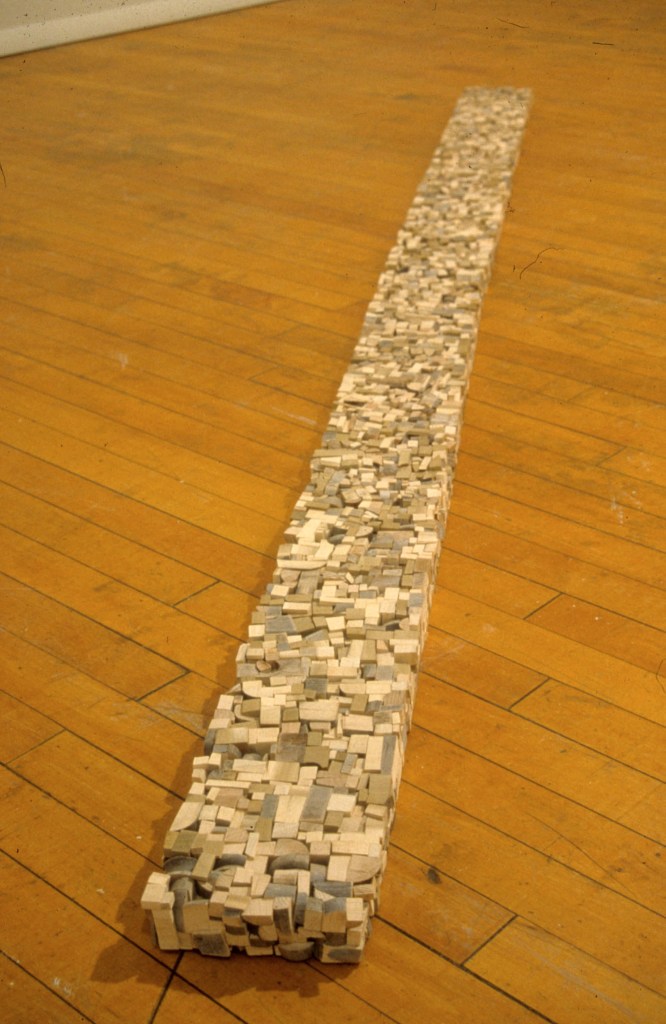

The original impetus for the “unmade” pieces came from an attempt to recreate an event from my childhood. To represent objects from the past, it occurred to me to move the objects back in time by reshaping them into their previous states. I cut apart an old wooden chair and a table with a worn finish and glued them back together into 4 x 4s and 2 x 6s. I crushed tin cans from the recycling bin under the wheels of my car, flattened them between heavy steel plates, and then soldered them together into a sheet of metal. I liked the way the objects were transformed, not just because they had appealing textures and forms, but because of the way the meaning had changed. They become at the same time about the past (memory) and about the future (death). Because all the space had been compressed and obliterated from the objects they once were, they were also about loss.

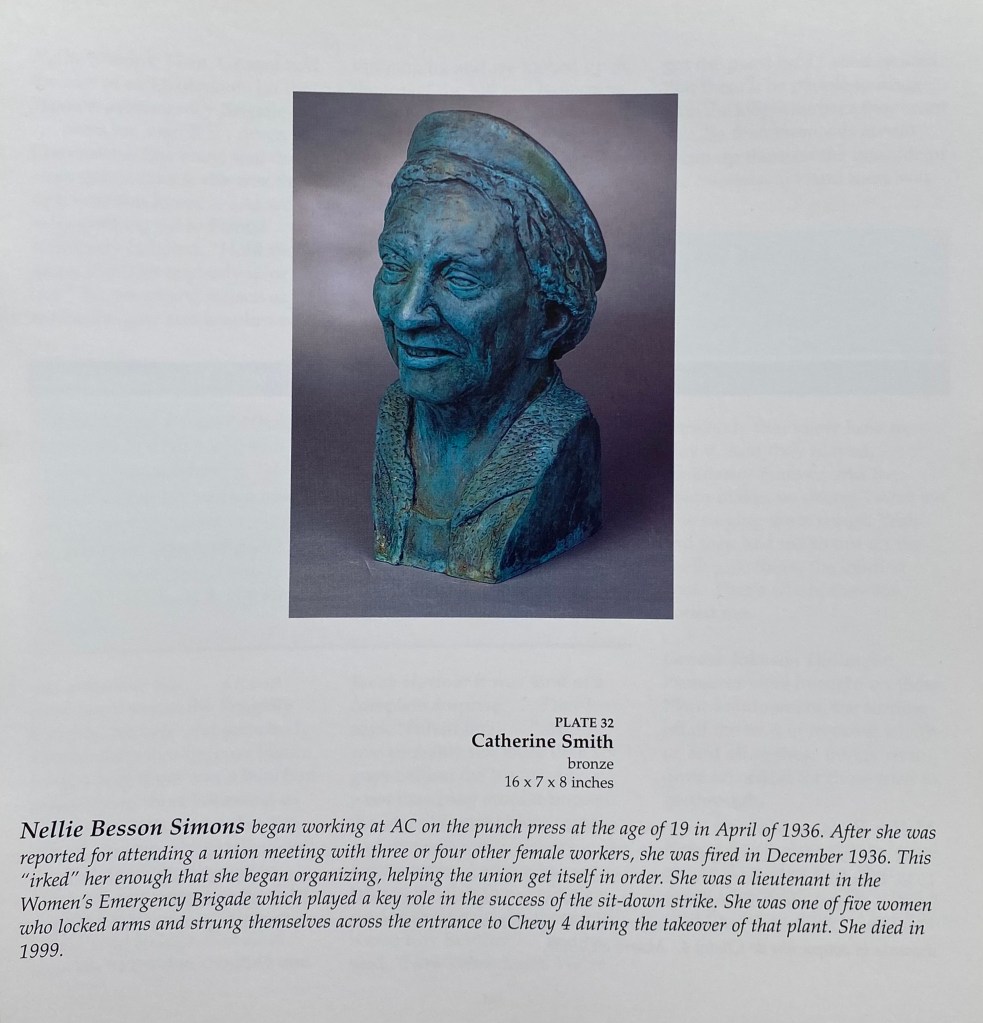

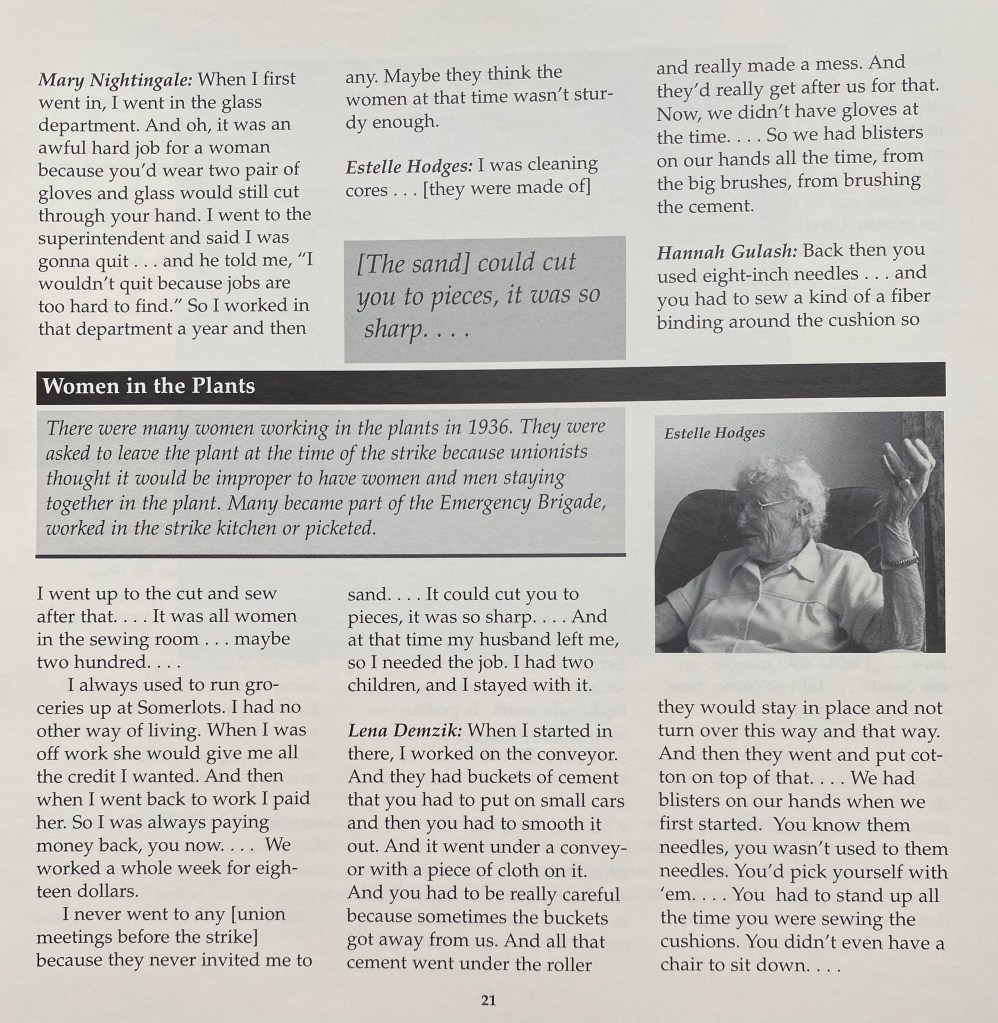

Portrait of Nellie Besson Simons

Bronze

Eighty years ago, Congress passed The National Labor Relations Act making it illegal for an employer to discriminate against workers who organized for the purpose of collective bargaining. Without the protection of the Wagner Act, the Flint Sit-Down Strike, which began in 1936, may not have succeeded. Prior to the success of the strike, workers had no voice in changing the deplorable conditions in the plants—long hours, foul air, unbearable heat, body-wrenching assembly line speedups, dangerous machinery, unfair piecework pay and abusive bosses. Nellie Simons, a lieutenant in the newly formed Women’s Emergency Brigade, along with Genora Johnson and other women, took on a significant role in the strike. Toward the end of the strike, this group of women held back police and vigilantes from stopping a plant takeover until a larger group of strike supporters could arrive. This last act crippled production and forced an end to the 44-day strike and led to the recognition of the union, making a significant gain for workers in all industries.

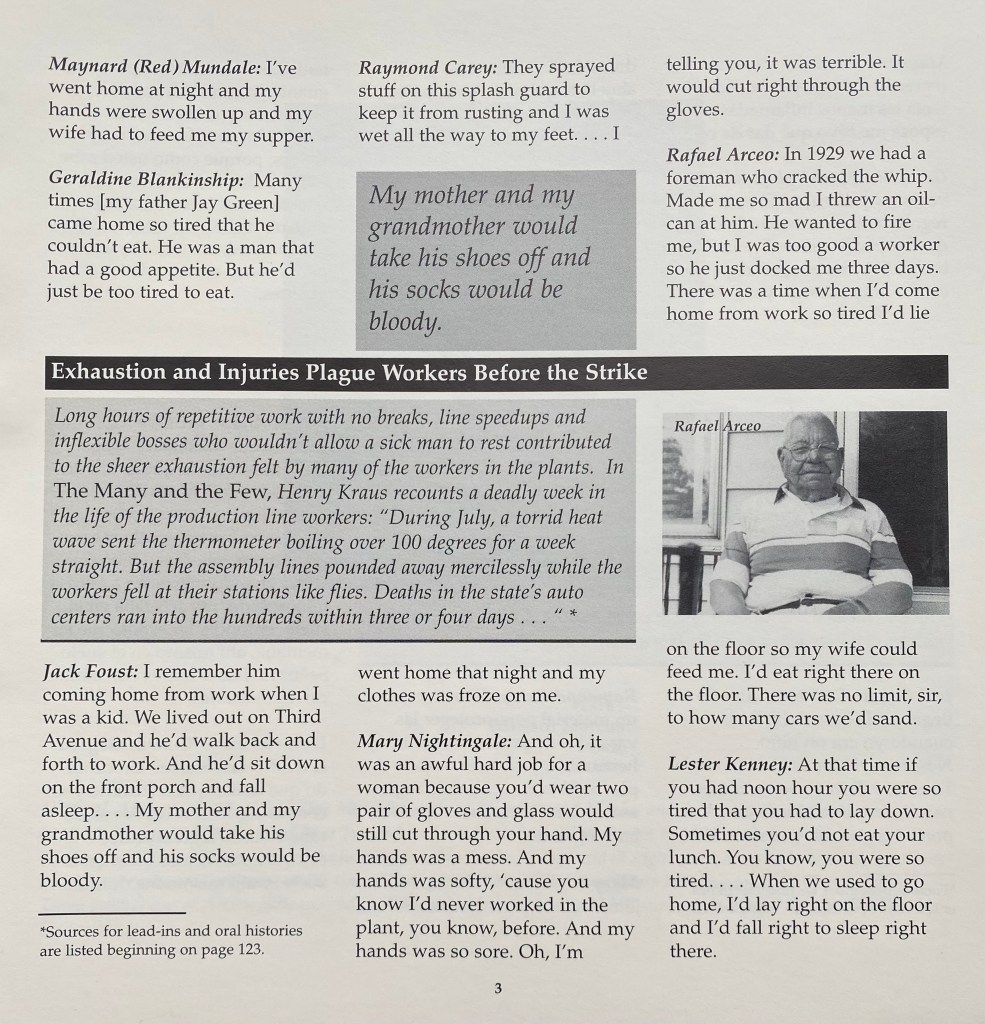

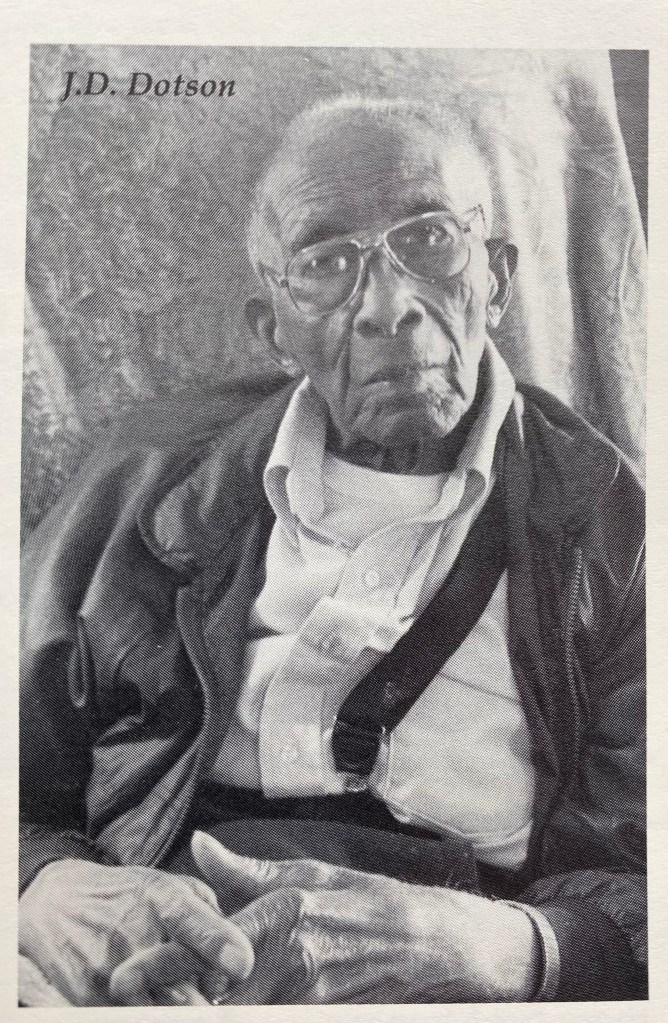

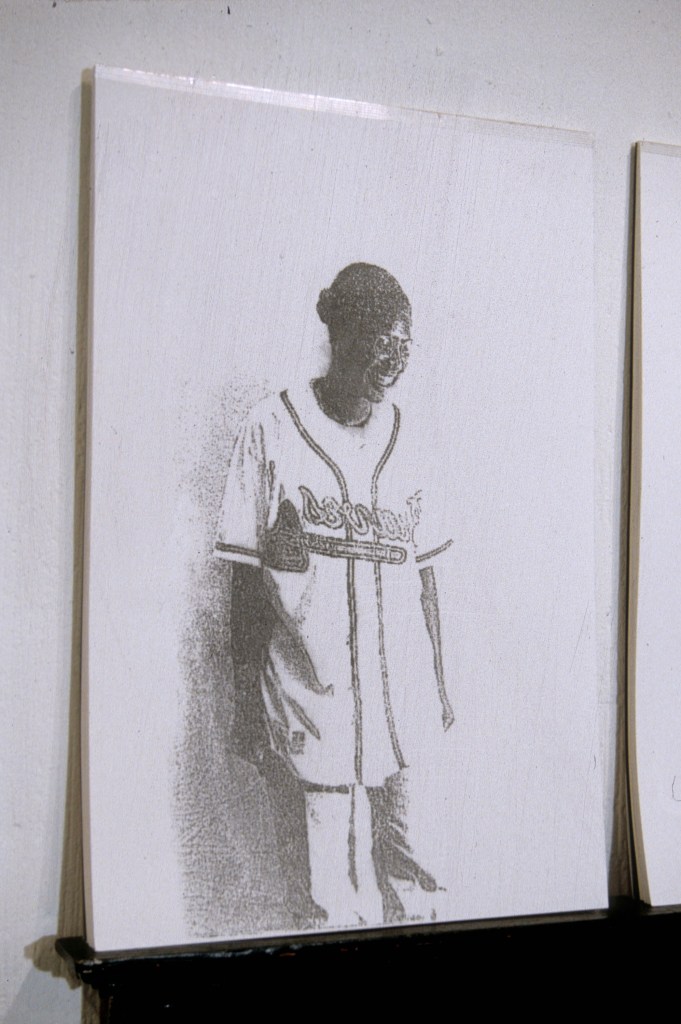

At Mott Community College in Flint, MI, a group of us developed a project meeting with surviving sitdowners and the people around them who helped the cause. We recorded their stories; I photographed them; and eventually we enlisted the help of artists to make portraits of those we spoke to. Below are some of pages from the book that resulted from this experience. An exhibition was held at the Greater Flint Arts Council Gallery in 1999.

At the time I took this photograph of J.D. Dotson he was the oldest living member of the UAW.

I also made this portrait bust of Ruben Burks, Secretary/Treasurer of the United Auto Worker Union.

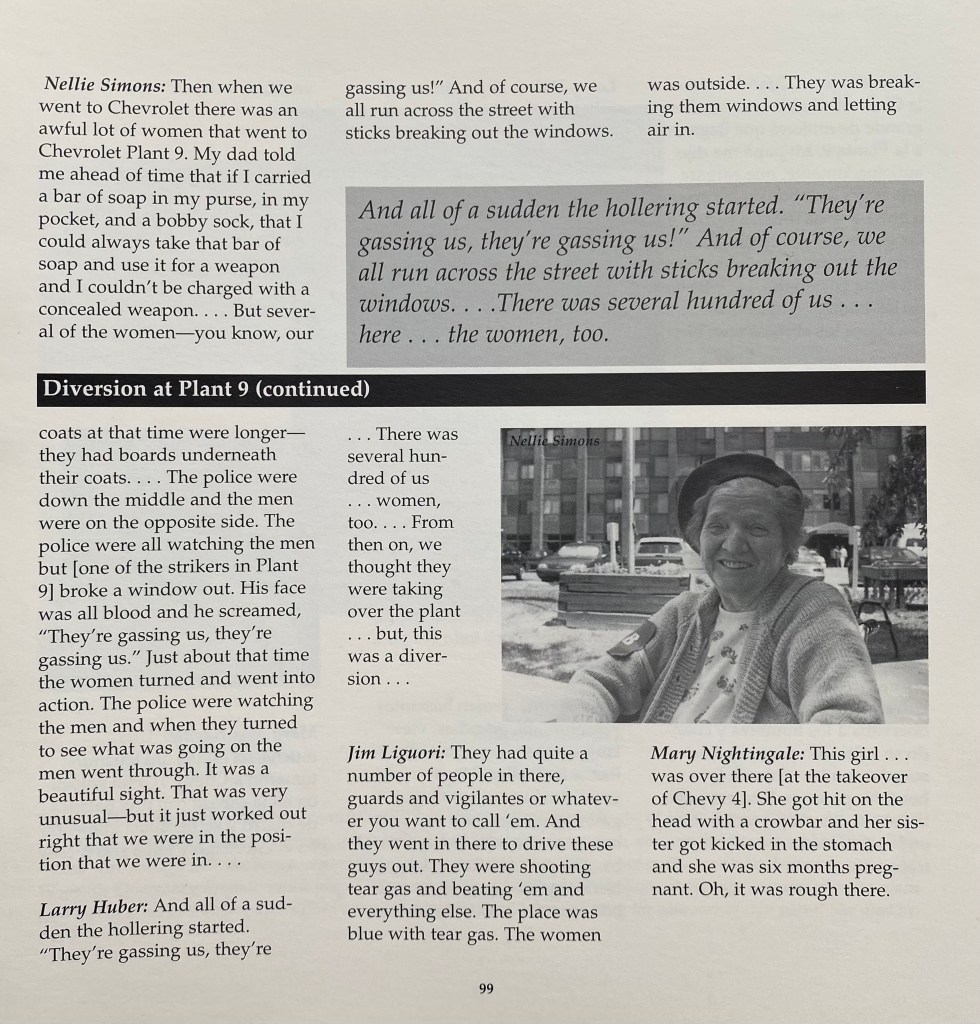

I began the stitched pieces while taking a month-long class on women in the Renaissance in Assissi, Italy in 1997. Most of the imagery comes from frescoes we studied, but two of the images are symbols for the female saints Claire and Catherine.

The process itself satirizes the female occupation of embroidery. The paper ground has been layered with alternating applications of graphite pencil and oil pastel until a rich solid surface is built up. The white floss is stitched roughly and, rather than being pristine, has become soiled during the work process.

Though the sources of the imagery are religious, gender and sexuality have been referenced in the simple iconic forms. A half-moon boat shape with a figure from a Giotto fresco records Mary Magdelene’s journey across the sea to become a hermit. The Madonna with one breast exposed, a common image during times of famine, has been represented with a hand and breast. A hair shirt depicts Saint Claire’s vow of poverty. A slit in the garment of the Madonna del Parto (the pregnant Madonna) covered timidly by a hand appears to be a gesture of protection of her sexuality. An image of the baby Jesus, devoid of context, has become just a reclining baby.

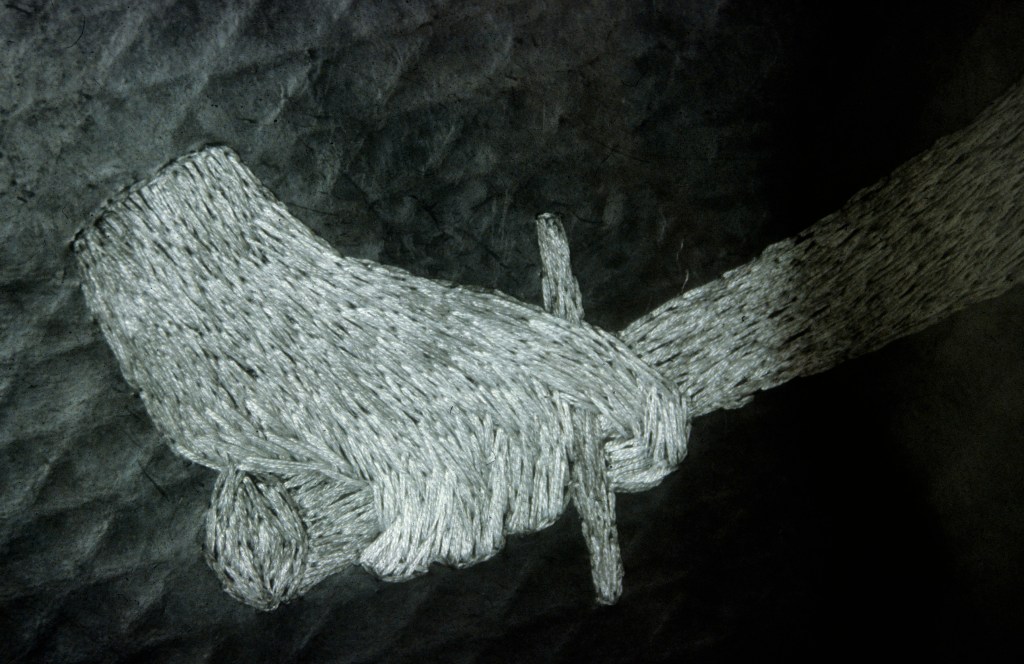

This installation at the Flint Institute of Art dealt with the beliefs of the community. The windows on the greenhouse forms revealed the beliefs of 10 women artists. Chalkboards around the room gave visitors the option to add their own comments. Also notebooks on a table in the gallery provided additional space for beliefs to be recorded. The pile of rocks reminded viewers of the violence that can be associated with openly revealing ones beliefs. Video screens behind the greenhouse form played images of fire which was related to the recent burnings of African American churches.

50-foot-long wood periscope with mirrors

Water trough, pump, hose, pipes and running water

Half-sphere of grass

Blue velvet cloth

Chair, binoculars

Found statue and vitrine

1995, altered 1996

A brief description of the piece: A 50-foot-long and 16 x 16-inch wide periscope winds through the gallery, making 10 turns. The viewer can sit at a chair and peer through the periscope at an image at the end which appears to be deep inside the wall. A pair of binoculars can be used to magnify the image. At the other end is a fragmented scene: rain, grass, sky. The view through the periscope is limited so that the tank and pipe system are not visible. Outside the gallery on the sidewalk is a 30-inch-high decaying statue that was found in a thrift store. A women appears to be escaping with her two children. They are carrying wheat in their arms. The statue is on a base of wood and steel and encased in a plexiglas container that is open at the top to the elements. The statue is partially flooded with water, which will accumulate during the length of the exhibition.

The principal form in The Study of Rain is a deep tunnel that provides a focus for vision, yet also removes the object of sight and study from its larger environment and the mechanism that sustains it. In itself, the rain falling on the grass is mere phenomena without apparent meaning and having perhaps a certain aesthetic appeal. The action happens outside the field of vision.

The wider view is available from the outset so that the viewer is aware of the limitations brought about by the narrower field. An even larger outlook is physically manifested in the traces of erosion from water etched onto the surface of a statue standing outside the gallery of a woman fleeing with her children.

Catherine Smith with Andrea Vidosh and Fred Wagonlander and the 120 art students of Central High School in Flint, Michigan. Writing workshops organized by Rebecca Sofa with Kristi Cummings, Denise DeLay, Lisa M. Smith, Kim McDonald, Mark Rabitz, Elizabeth Dickens and Veronica Smith. Special thanks to Doug Hoppa, Tonya Jaeger and Kathryn Pekarek

I have been making a series of works that use, as their central idea, the recycling of useable materials from art object back to functional object. They are made up of things that sculpture or installations can be constructed from and then after the show is over can be dismantled and used as they were originally intended. Among these pieces have been: a kitchen form made from stacked canned foods that later went to a food bank; a bathtub with running water, filled with electric frying pans, that were donated to a women’s shelter; and two large forms made up of dishracks laced together, and weighted down by cast iron frying pans. These works have been funded through donations, grants, and honorarium.

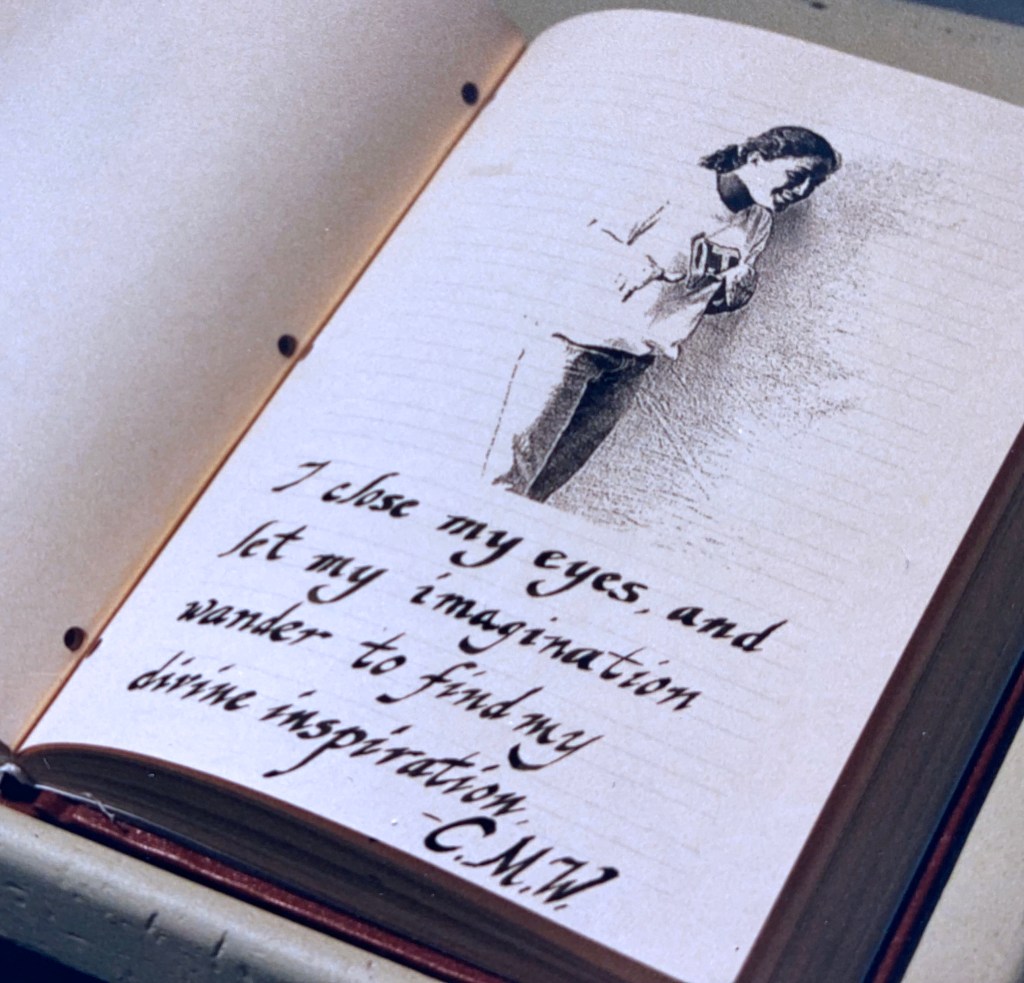

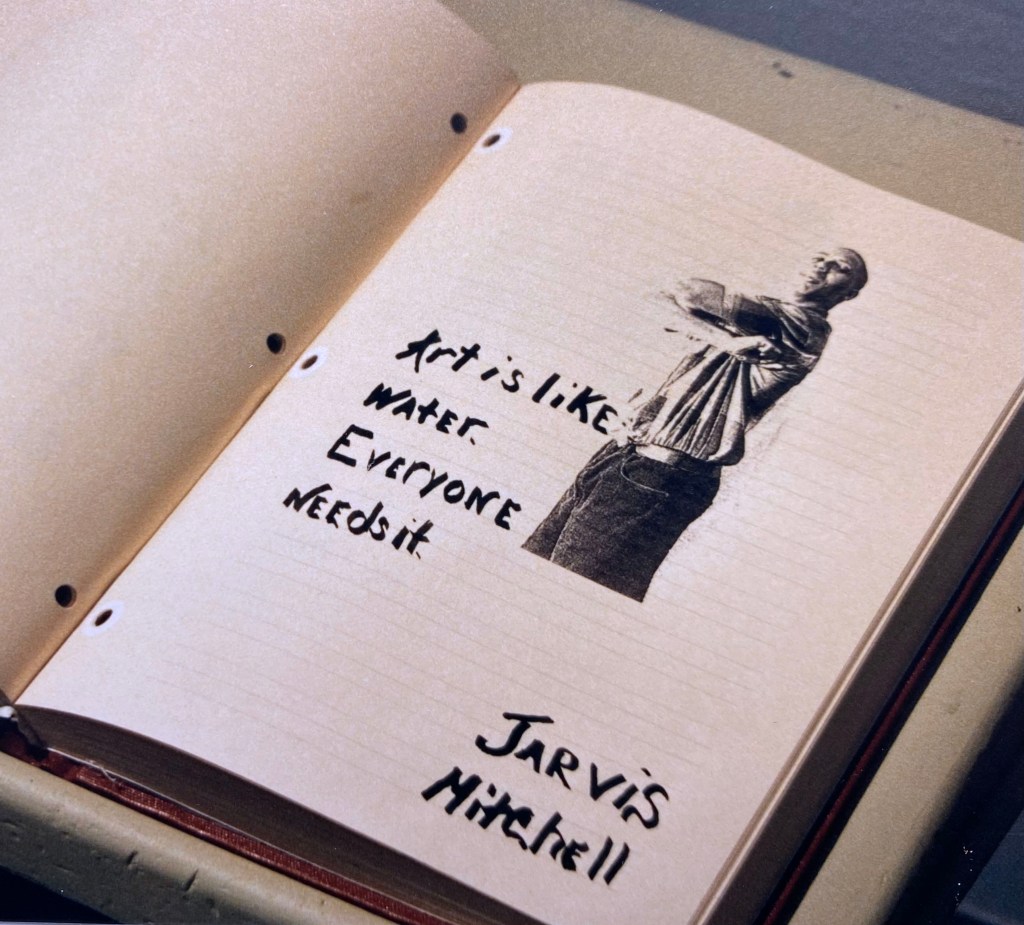

This piece is made up of art supplies that will not be consumed in the art making process. The 120 homemade sketchbooks that make up Blank Pages will go to the art students at Central High School who also participated by making the Xerox transfers of their portraits onto the covers of the books, and by writing artist statements while learning calligraphy. Special thanks go to the instructors: Andrea Vidosh for all her enthusiasm, motivational gifts and hard work and to Fred Wagonlander for his enthusiastic support, hard work and ability to run a quality program on what amounts to a mere $5/per student/per year in supplies. These young artists need all the support we can give them. It was a pleasure to work with them on this project.

Wood and Plexiglass structure

Rubber rug, photograph of curtains, cement seat

Scope

Steel stairs on casters

This piece was made specifically for the Kresge Art Museum in East Lansing, Michigan for the Michigan Biennial Exhibition. The large “vitrine” is big enough to enclose and isolate the viewer, who is then free to privately view artwork in the museum through a telescope. As the museum goer stands in the structure, they are both the viewer and the viewed. The previous viewing apparatus, built at the Mattress Factory in Pittsburgh, allowed the viewer to see inside the gallery without actually entering the space. This meant that residents in the community who might feel uncomfortable in an art space had the freedom to participate without actually having to enter the space. The structure of this piece protects in a similar way by creating a homelike atmosphere with rug, seat and curtains that could seem more comforting than the harsh lights and open spaces of the museum, despite the harsher materials those objects are made from (rubber, cement, plastic film.

Idle Accord

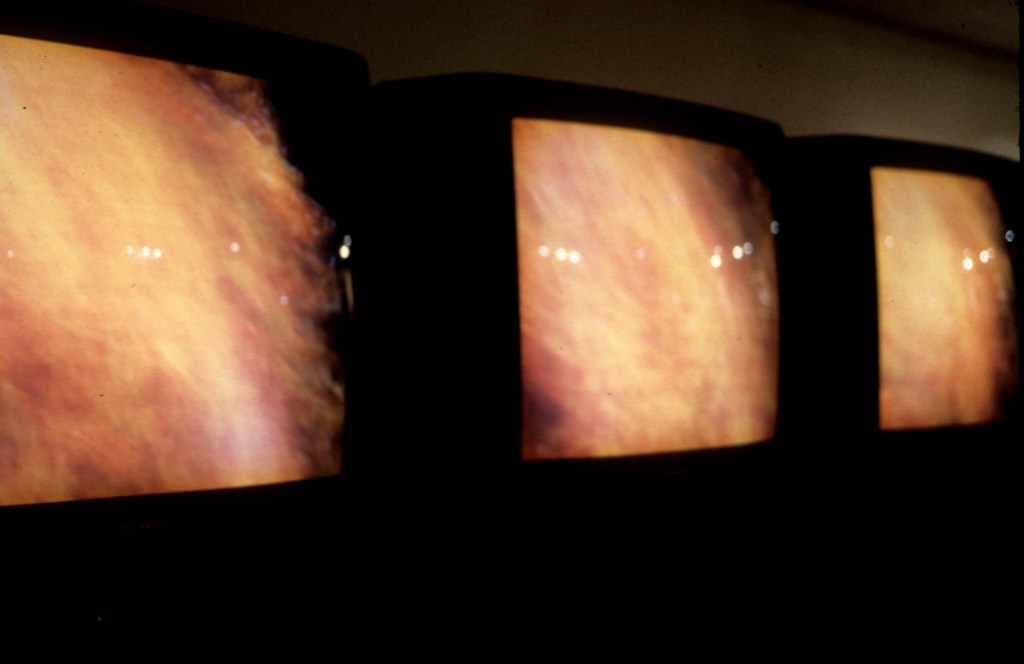

A video collaboration with Cathy Gasser (Ono), Melissa Goldstein, and Catherine Smith

3 video monitors

1995

This is the last in a group of collaborations with women I studied with at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. By this time we were scattered throughout the country: Cathy Gasser was in Kansas; Melissa was in New York; I was in Michigan. The internet was in its infancy though we did communicate through email. Each of us videotaped ourselves stressed out on a comfortable couch or bed. We had taped a conversation we had the previous summer when we were together in New York City. The piece consists of three monitors with the images of each of us and the conversation in text ran across the bottom of the screens. This piece was exhibited in Kansas, Michigan and Illinois.

Here is a sampling of the text:

It’s such slacker art in a way. It is. You know what I mean? I don’t mind that, I mean. I think that’s being honest, I mean, you know all the work in graduate school that you could instead write an essay about? Oh definitely. You could write an essay about this; this is a little bit conceptual, right? Highly, I mean, I think slacker art is conceptual, just in it’s not being, it’s being. I mean like Sean Landers’ kind of slacker art. I don’t know his work, what’s his work like? He talks about his dick. He takes pictures of himself on rocks naked. His whole body, or just his dick? It’s adolescent male art to me. I think it should be something really serious, like a car wreck. Serious involves like, death. Well, it’s something that moves you, like who are you going to vote for President? You are talking about things that are not personal. Right, okay, I talk about a dead person in the family. This is not personal. Aunt Heloise? It’s not personal that Aunt Heloise was blown away by a Mac truck in the morning. That is personal. You mean serious is not personal? What if little kids were having our conversation? Then it’s like Gary Hill. The impenetrable book. A book about color theory. Well, what is a situation in which three people would sit down and have a fairly serious conversation? Probably about . . . their job, their love life, their family. A disagreement they were having. We talk about art, that’s not serious, even though I got into a huge fight and told someone I never wanted to speak to them again a month ago. You were talking about art? Yup, I was talking about fucking painting and DeKooning, DeKooning, DeKooning, DeKooning. I was thinking of making. . . I found all these boats made out of ummmmm, burnt matches, and I was thinking that would be really fun, maybe I will just make a hundred of those and do an installation like that and they would be like folk art and everyone would want them, and afterwards I would sell them for like a hundred bucks, ‘cause everyone loves those matchbook boats . . . and they are so nice. I mean that is what people want. I’ve never seen them, but I believe you are right. They are made by prisoners. I think I would make about one a week. I could make like fifty a year. And people could write an essay and talk about what a prisoner you are. Yeah, I’m a prisoner of my matches.